When I read Roberta Smith's review (New York Times' co-chief art critic) of the 2015 Picasso Sculpture exhibition at the MoMa, which she praised as being "one of the best exhibitions you'll ever see at the Museum of Modern Art", I wished I could go see it. At the time, I had just moved to Glasgow and a trip to New York was definitely not on the cards. In 2016, the exhibition was hosted at the Musée Picasso in Paris and, although I was now in Europe, I couldn't visit it either. My third attempt was proverbially lucky as Picasso. Sculptures ultimately traveled to me and is now on view in Brussels at the BOZAR/Center For Fine Arts, the Belgian location for the show's third dazzling iteration.

As suggested in the eponymous title, Picasso. Sculptures gives an insight into the prolific Spanish painter's lesser known three-dimensional works. First of a kind in Belgium, this large exhibition is organized both chronologically and thematically and unfolds across eleven dedicated rooms.

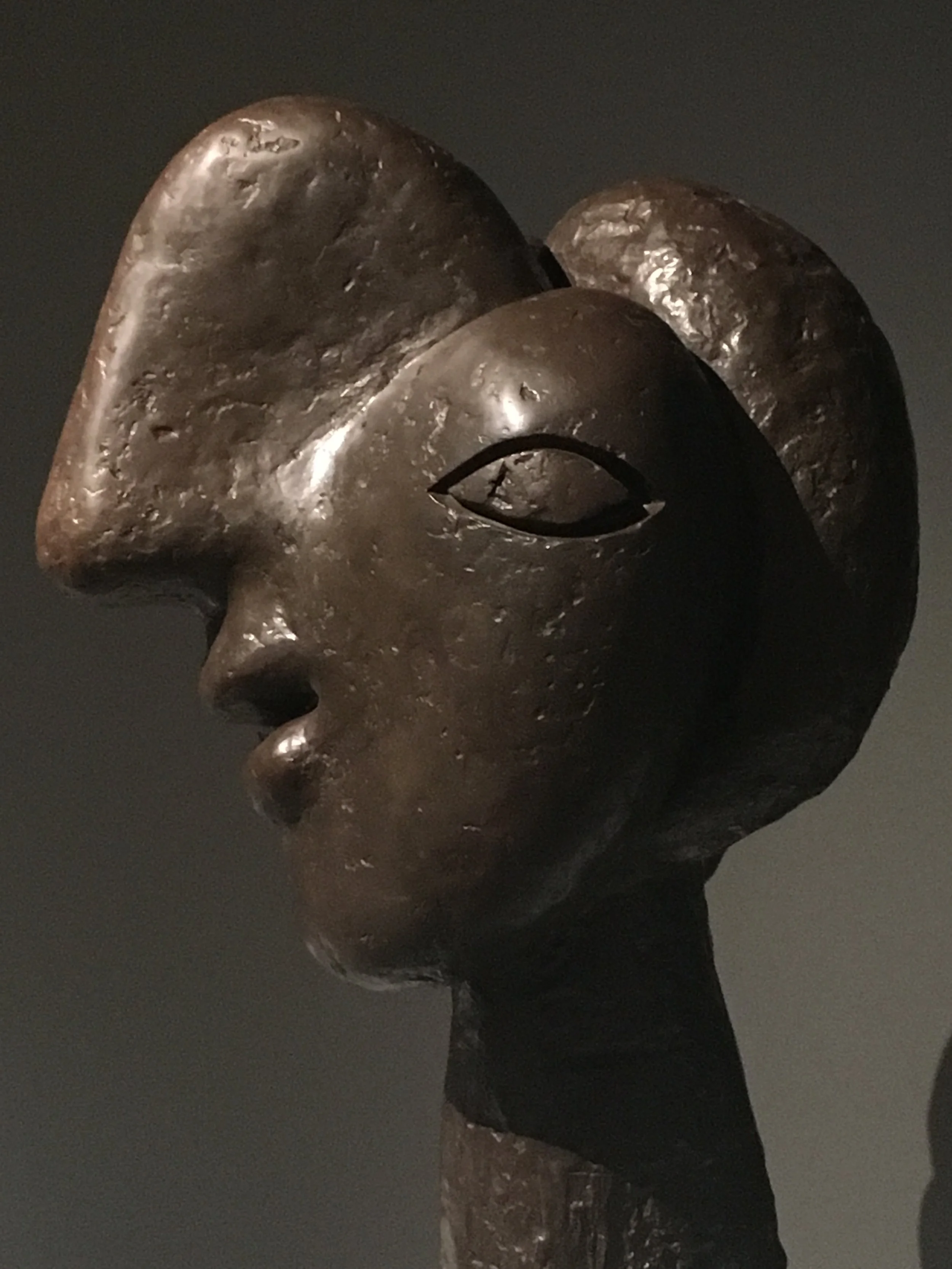

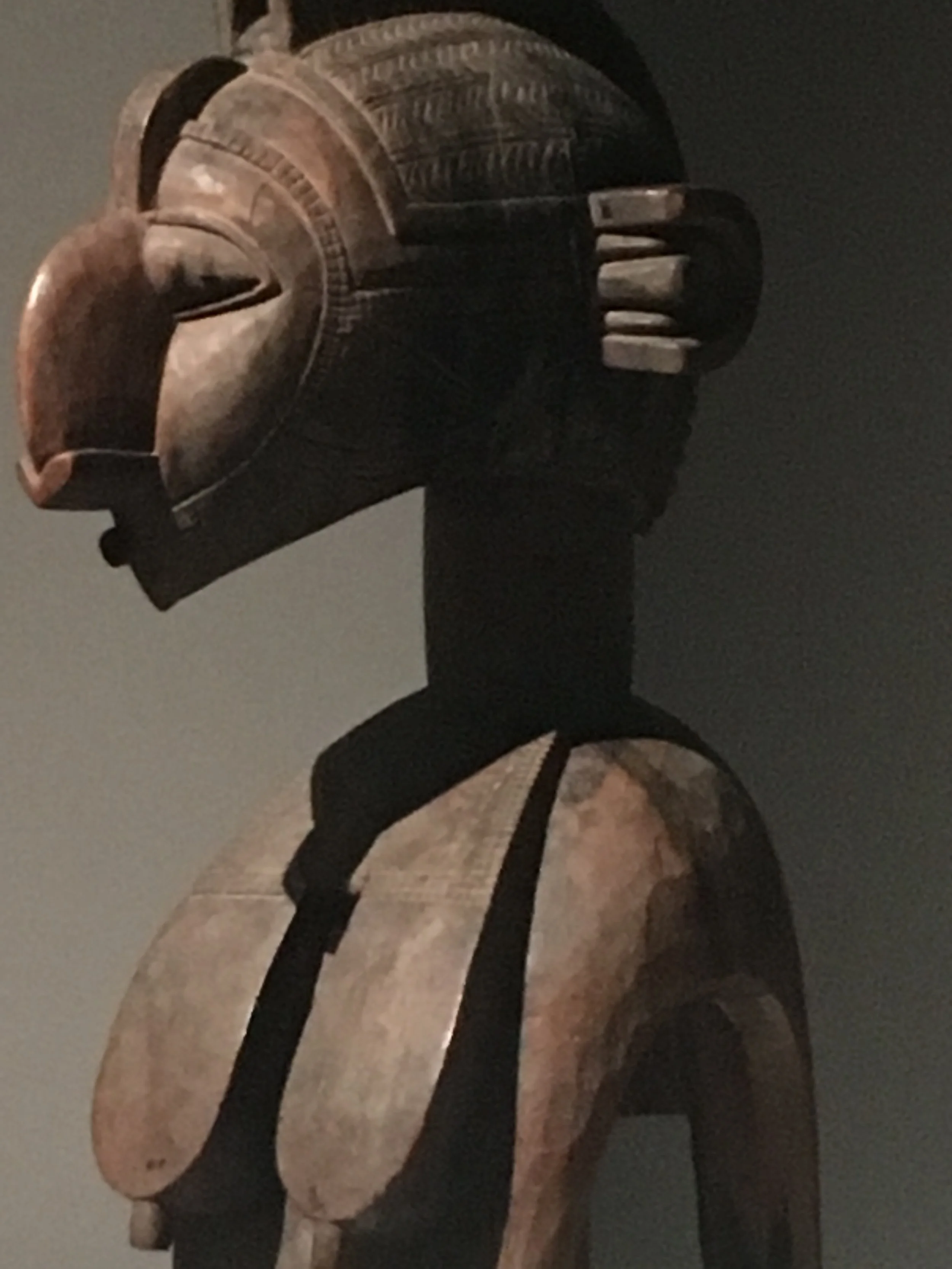

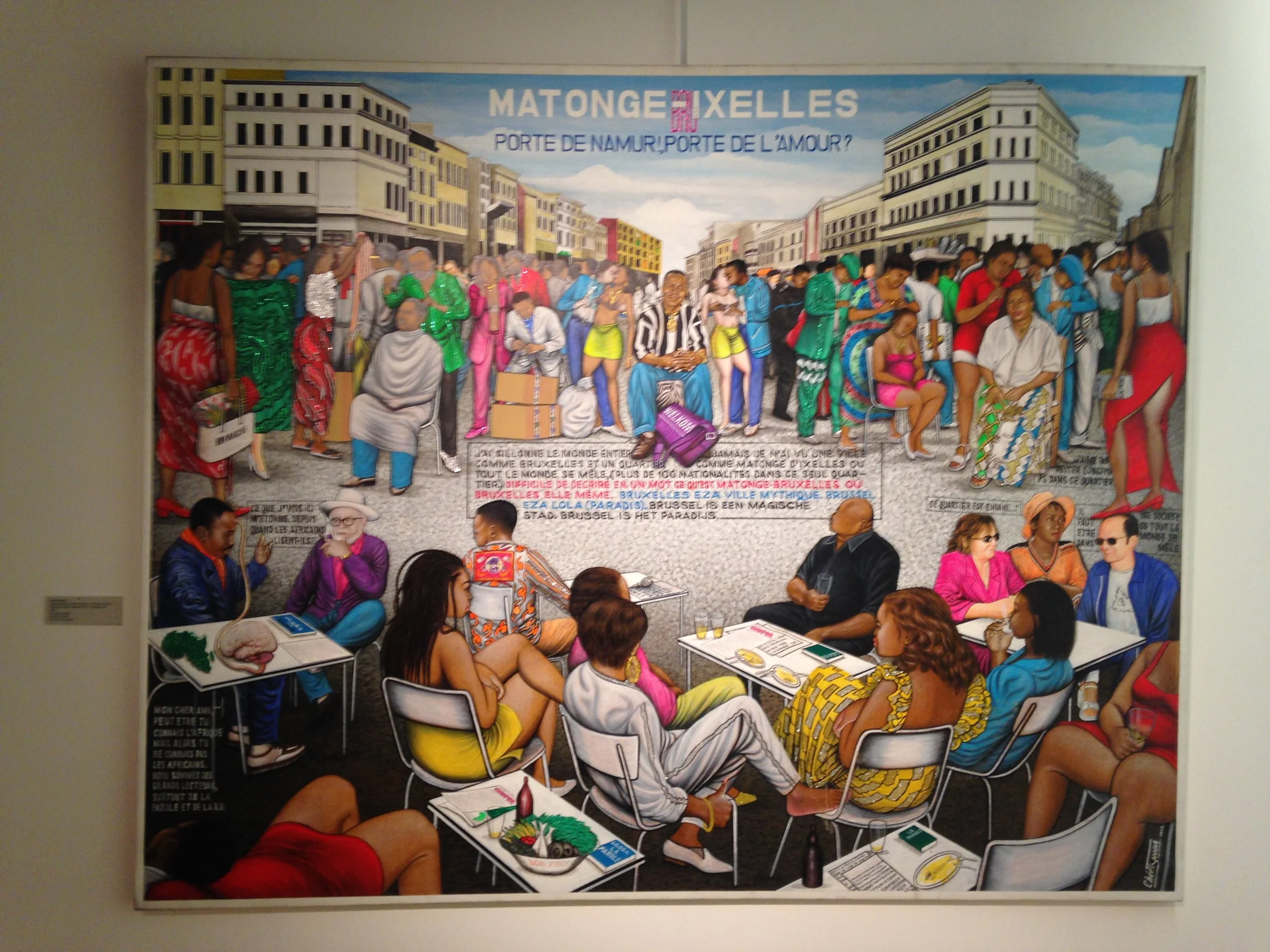

About eighty of Pablo Ruiz Picasso's sculptures are on display in the Belgian edition. The Brussels' show differs from the ones in New York and in Paris most notably in its inclusion of fifteen of Picasso's paintings. The sculptures are also shown alongside African masks and miniature Iberian bronze figures from Picasso's personal collection and beside his own ceramics. Céline Godefroy's and Virginie Perdrisot's curatorial decision to pair Picasso's sculptures with the above-mentioned works stresses the influence that African and Iberian art had on the artist (who first discovered them in 1906-1907) and incites the viewer to pay attention to the formal parallels, singularities and cross-references between the various artworks on display. These combinations lay the ground for a unique, informative and pro-active viewing experience.

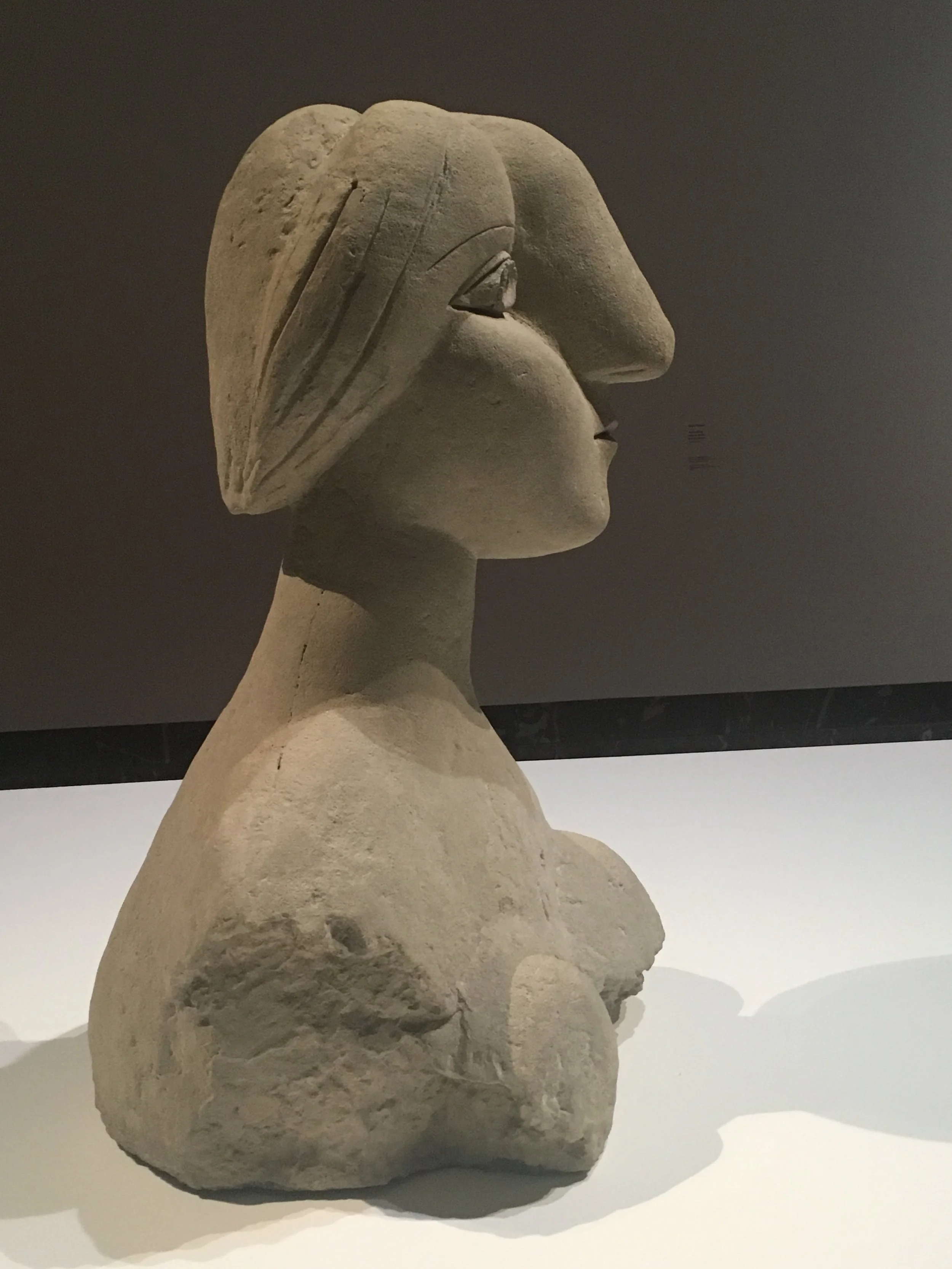

Upon entering the exhibition, the visitor is greeted by Bust of a Woman (1931), a frontally displayed cement sculpture whose expressive engraved eyes seem to look right through you. The bust is positioned on a large rectangular plinth in the center of the room and the viewer is forced to circle around the sculpture in order to proceed with her/his visit. As one walks around it, the bust's frontal female face becomes a profile, a three-dimensional quasi-rendering of the bust depicted in The Sculptor, an oil painting on board from the same year, portraying an artist in his studio, hung on the opposite wall. This introductory pairing sets the tone for the rest of the exhibition where the viewer is encouraged to engage with the works from multiple viewpoints, to actively shift her/his perspective in order to absorb the sculptures' volumes and to draw connections between painting and sculpture as her/his eye gleefully jumps from representations in three and in two dimensions.

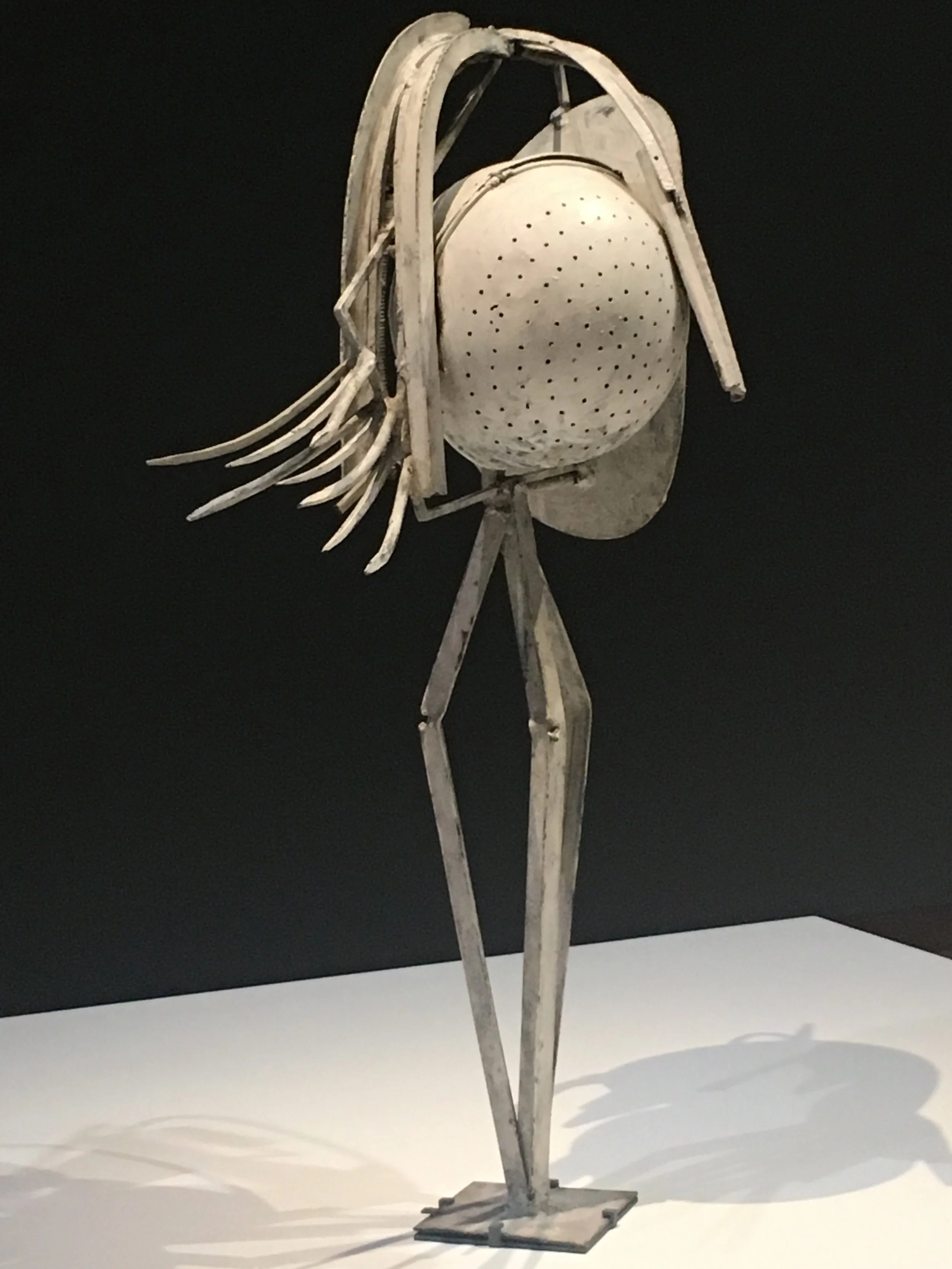

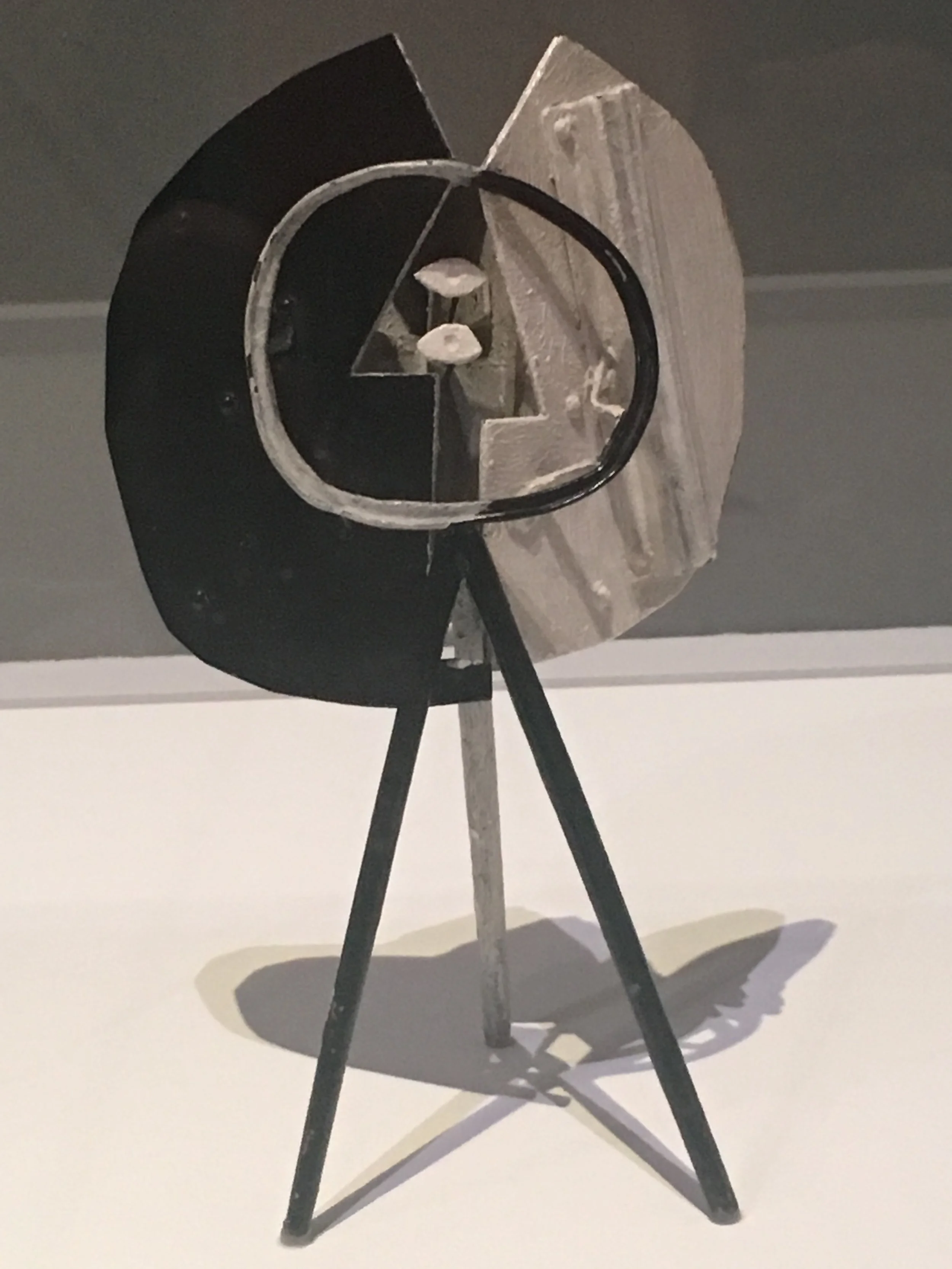

The emphasis of the show is on Picasso's multi-faceted and inventive approach to a medium that he never trained for. The sculptures span from 1902 (Femme Assise) to the 1960s. As one progresses chronologically through the rooms, one follows the evolution of the painter's experiments with the medium as he acquires new techniques. I was struck by the variety of materials used by the artist in his constant search for new forms. The sculptures brought together range from being modeled in bronze to being carved in wood (Figure, 1907) to becoming assemblages of painted metal hung on the wall similarly to a painting (Violin, 1915) or to incorporating "ready-made" objects such as a strainer (Woman Head, 1931) or a seat and handlebar made of leather in Bull's Head (1942).

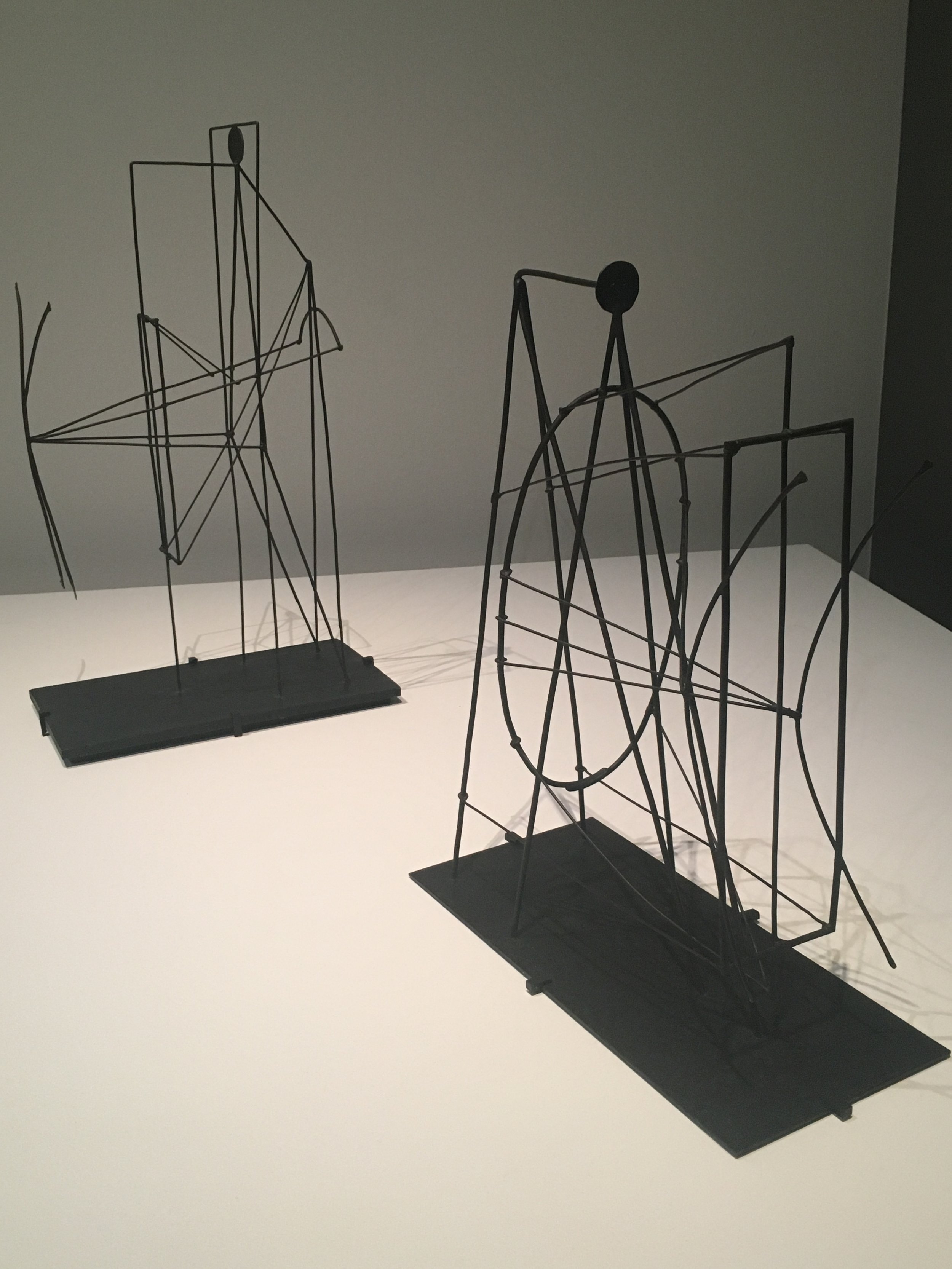

While Picasso's first experiments in three dimensions are figurative, the painter's cubist breakthroughs are progressively transferred into his sculptures, which become more akin to deconstructed "drawings in space". In cutting through the block of material he uses, Picasso allows his sculptures to stand in relationship to the space rather than simply in it (Figure, 1928). The bold black lines in his paintings translate into sculptures of void and transparency.

My personal highlights include the works Picasso made in his Boisgeloup studio, the ceramics that he painted over at the Atelier Madoura in Vallauris in the South of France and his playful sculptures in painted iron and sheet metal.

Picasso. Sculptures is a welcome opportunity to discover the three-dimensional work of one of the foremost painters of the 20th century and to gain insight into the interrelationships between his sculpture and his painting.

Picasso. Sculptures, BOZAR/Center for Fine Arts, Rue Ravenstein 23, 1000 Brussels, Belgium. On view until March 5, 2017.

Copyright © 2016, Zoé Schreiber